Caribou Wharf Herring Fishing

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family Clupeidae.

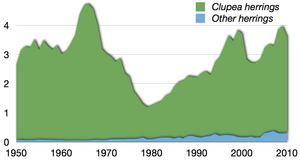

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast. The most abundant and commercially important species belong to the genus Clupea, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacificand the North Atlantic oceans, including the Baltic Sea, as well as off the west coast of South America. Three species of Clupea are recognised, and provide about 90% of all herrings captured in fisheries. Most abundant of all is the Atlantic herring, providing over half of all herring capture. Fishes called herring are also found in the Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, and Bay of Bengal.

Herring played a pivotal role in the history of marine fisheries in Europe,[2] and early in the 20th century, their study was fundamental to the evolution of fisheries science.[3][4] These oily fish[5] also have a long history as an important food fish, and are often salted, smoked, or pickled.

At least one stock of Atlantic herring spawns in every month of the year. Each spawns at a different time and place (spring, summer, autumn, and winter herrings). Greenland populations spawn in 0–5 m (0–16 ft) of water, while North Sea (bank) herrings spawn at down to 200 m (660 ft) in autumn. Eggs are laid on the sea bed, on rock, stones, gravel, sand or beds of algae. Females may deposit from 20,000 to 40,000 eggs, according to age and size, averaging about 30,000. In sexually mature herring, the genital organs grow before spawning, reaching about one-fifth of its total weight.

The eggs sink to the bottom, where they stick in layers or clumps to gravel, seaweed, or stones, by means of their mucous coating, or to any other objects on which they chance to settle.

If the egg layers are too thick they suffer from oxygen depletion and often die, entangled in a maze of mucus. They need substantial water microturbulence, generally provided by wave action or coastal currents. Survival is highest in crevices and behind solid structures, because predators feast on openly exposed eggs. The individual eggs are 1 to 1.4 mm (0.039 to 0.055 in) in diameter, depending on the size of the parent fish and also on the local race. Incubation time is about 40 days at 3 °C (37 °F), 15 days at 7 °C (45 °F), or 11 days at 10 °C (50 °F). Eggs die at temperatures above 19 °C (66 °F).

The larvae are 5 to 6 mm (0.20 to 0.24 in) long at hatching, with a small yolk sac that is absorbed by the time the larvae reach 10 mm (0.39 in). Only the eyes are well pigmented. The rest of the body is nearly transparent, virtually invisible under water and in natural lighting conditions.

The dorsal fin forms at 15 to 17 mm (0.59 to 0.67 in), the anal fin at about 30 mm (1.2 in)—the ventral fins are visible and the tail becomes well forked at 30 to 35 mm (1.4 in)— at about 40 mm (1.6 in), the larva begins to look like a herring.

The larvae are very slender and can easily be distinguished from all other young fish of their range by the location of the vent, which lies close to the base of the tail, but distinguishing clupeoids one from another in their early stages requires critical examination, especially telling herring from sprats.

At one year, they are about 10 cm (3.9 in) long, and they first spawn at three years.

Herrings are a prominent converter of zooplankton into fish, consuming copepods, arrow worms, pelagic amphipods, mysids, and krill in the pelagic zone. Conversely, they are a central prey item or forage fish for higher trophic levels. The reasons for this success is still enigmatic; one speculation attributes their dominance to the huge, extremely fast cruising schools they inhabit.

Herring feed on phytoplankton, and as they mature, they start to consume larger organisms. They also feed on zooplankton, tiny animals found in oceanic surface waters, and small fish and fish larvae. Copepods and other tiny crustaceans are the most common zooplankton eaten by herring. During daylight, herring stay in the safety of deep water, feeding at the surface only at night when the chance of being seen by predators is less. They swim along with their mouths open, filtering the plankton from the water as it passes through their gills. Young herring mostly hunt copepods individually, by means of "particulate feeding" or "raptorial feeding",[110] a feeding method also used by adult herring on larger prey items like krill. If prey concentrations reach very high levels, as in microlayers, at fronts, or directly below the surface, herring become filter feeders, driving several meters forward with wide open mouth and far expanded opercula, then closing and cleaning the gill rakers for a few milliseconds.

Copepods, the primary zooplankton, are a major item on the forage fish menu. Copepods are typically 1 to 2 mm (0.04 to 0.08 in) long, with a teardrop-shaped body. Some scientists say they form the largest animal biomass on the planet.[111] Copepods are very alert and evasive. They have large antennae (see photo below left). When they spread their antennae, they can sense the pressure wave from an approaching fish and jump with great speed over a few centimetres. If copepod concentrations reach high levels, schooling herrings adopt a method called ram feeding. In the photo below, herring ram feed on a school of copepods. They swim with their mouths wide open and their perculae fully expanded.

The fish swim in a grid where the distance between them is the same as the jump length of their prey, as indicated in the animation above right. In the animation, juvenile herring hunt the copepods in this synchronised way. The copepods sense with their antennae the pressure wave of an approaching herring and react with a fast escape jump. The length of the jump is fairly constant. The fish align themselves in a grid with this characteristic jump length. A copepod can dart about 80 times before it tires. After a jump, it takes it 60 milliseconds to spread its antennae again, and this time delay becomes its undoing, as the almost endless stream of herring allows a herring to eventually snap the copepod. A single juvenile herring could never catch a large copepod.[110]

Other pelagic prey eaten by herring includes fish eggs, larval snails, diatoms by herring larvae below 20 mm (0.79 in), tintinnids by larvae below 45 mm (1.8 in), molluscanlarvae, menhaden larvae, krill, mysids, smaller fishes, pteropods, annelids, Calanus spp., Centropagidae, and Meganyctiphanes norvegica.

Herrings, along with Atlantic cod and sprat, are the most important commercial species to humans in the Baltic Sea.[112] The analysis of the stomach contents of these fish indicate Atlantic cod is the top predator, preying on the herring and sprat.[112][113] Sprat are competitive with herring for the same food resources. This is evident in the two species' vertical migration in the Baltic Sea, where they compete for the limited zooplankton available and necessary for their survival.[114] Sprat are highly selective in their diet and eat only zooplankton, while herring are more eclectic, adjusting their diet as they grow in size.[114] In the Baltic, copepods of the genus Acartia can be present in large numbers. However, they are small in size with a high escape response, so herring and sprat avoid trying to catch them. These copepods also tend to dwell more in surface waters, whereas herring and sprat, especially during the day, tend to dwell in deeper waters.[114]

Herring has been a staple food source since at least 3000 BC. The fish is served numerous ways, and many regional recipes are used: eaten raw, fermented, pickled, or cured by other techniques, such as being smoked as kippers.

Herring are very high in the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA.[122] They are a source of vitamin D.[123]

Water pollution influences the amount of herring that may be safely consumed. For example, large Baltic herring slightly exceeds recommended limits with respect to PCB and dioxin, although some sources point out that the cancer-reducing effect of omega-3 fatty acids is statistically stronger than the cancer-causing effect of PCBs and dioxins.[124] The contaminant levels depend on the age of the fish which can be inferred from their size. Baltic herrings larger than 17 cm may be eaten twice a month, while herrings smaller than 17 cm can be eaten freely.[125] Mercury in fish also influences the amount of fish that women who are pregnant or planning to be pregnant within the next one or two years may safely eat.

Adult herring are harvested for their flesh and eggs, and they are often used as baitfish. The trade in herring is an important sector of many national economies. In Europe, the fish has been called the "silver of the sea", and its trade has been so significant to many countries that it has been regarded as the most commercially important fishery in history.[120]

Environmental Defense have suggested that the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) fishery is an environmentally responsible fishery.[121]

Source: Wikipedia

Comments